Luisais Taveras

HONS 2011J – Spanish Civil War in Literature and Film

Final Essay

Professor Hernández-Ojeda

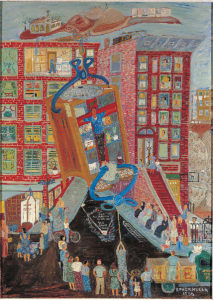

Raphaele “Ralph” Fasanella

Personal Statement (250)

My knowledge or awareness of the Spanish Civil War was significantly limited to non-existent prior to taking this course. Overall, war and its historical figures are often displayed in a one-dimensional manner for the learner, taking away the human essence of lived experiences and the acknowledgment of the larger loss over its proclaimed victory. Consequently, when presented with the task to write a piece on a volunteer from the Abraham Lincoln Brigade for their participation in the Spanish Civil War, I envisioned conveying the life of a woman whose trajectory resembled the career path I desire to one day have. Nonetheless, my quest brought me to Raphaele Fasanella, whose only similarities we shared included being born in the same month, our upbringing in the Bronx, and lack of formal education in the arts, but unlike him, I will not go on to have my work displayed in exhibits across the United States. Due to COVID-19, access to physical documents had become unattainable and created some hurdles in connecting the dots between certain life events and their chronological occurrence. Regardless, I was able to form a well-rounded view of Raphaele’s life through the analysis of biographies written about him, his paintings, and a recording of an interview he had done from the Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives Oral History Collection.

This experience came full circle when one afternoon I was met with the contagious laughter of Marc Fasanella, the son of Raphaele and whose father had lovingly given him the nickname of “old man,” with Marc endearingly calling him in return “Ralphie.” Marc, a pure reflection of his father’s generosity, in our interview shared with me family anecdotes, honest insight into Raphaele’s role outside of a painter and activist, and provided me a safe sanctuary to curiously learn about Raphaele through vast literary pieces and articles. The more I began to contextualize Raphaele’s colorful life as not just a testament to his work as a painter but his long journey towards social change, it allowed me to view this project as not only an assignment but my civil duty. Raphaele’s legacy of political activism confronted notions of traditional mediums, language, and social class as he made his contributions, be known in both the United States and Spain.

An Activist’s Humble Beginning (1914-1936)

Raphaele Fasanella, more commonly known as Ralph due to the Anglo-Saxons’ changing of his birth name, was born on September 2nd of 1914 (Johnson). Raphaele went on to later adopt Labor Day as his birthday, regardless of the day it fell in because of his profound connection to labor workers, which translated onto his work (Fasanella, Marc). Raphaele’s immigrant parents, Guiseppe (Joe) Fasanella and Ginevra (Spagnoletti) Fasanella left Lavello, province of Apulia, Italy in 1911 to escape the growing political conflicts in Italy that resulted in the Italo-Turkish War. Once in the United States with Raphaele’s older brother Sabino, Raphaele’s parents settled in the Fordham section of the Bronx, New York, where they go on to welcome Raphaele’s older sister Angelina in 1912, Raphaele’s older brother Tomaso in 1913, Raphaele himself in 1914, Raphaele’s younger sister Theresa in 1915 and Raphaele’s younger brother Nicolo in 1916 (Fasanella and Umberger).

Raphael’s parents embodied the many Italian immigrants striving to succeed in a foreign country. Raphaele’s father, Guiseppe (Joe), delivered ice to apartments in Brooklyn, while Raphaele’s mother Ginevra, worked in the garment industry where she made the holes in the buttons. Ginevra’s activism grew increasingly since her arrival to the United States, where she began to attend anti-fascist and trade union causes. At approximately eight years old, Raphaele began to accompany his father to deliver ice by the use of a horse-driven wagon, initiating his awareness of the strenuous demands of labor (“Fasanella, Ralph”). In his mother, Raphaele saw a strong sense of social justice and political awareness through her anti-fascist activism. These dualities of experiences cultivate Ralph an identity with the working class. In Raphaele’s home, Italian music played in the background of loud gatherings, which permitted Ralph an avenue to embrace his Italian background and not shy away from proudly proclaiming his immigrant roots (Johnson).

Raphaele described himself as a “tough and rough” kid, who over time became a good street fighter (Johnson). Even at a young age, Raphaele viewed attending school as a place where you are expected to follow orders, accept the physical punishments of any action that deviated from what was expected of you, and a lack of creative input which strongly went against Raphaele’s values. Aside from the negative connotation attached with Raphaele’s character, he developed a social consciousness in protecting those that could not protect themselves as he did when his Jewish friend when he was being picked on. In his parents working all day and there being no one home, gave Raphaele the liberty to spend his days playing in yards, running around, and developing a habit of smoking. Raphaele’s education and life experiences began to take place outside of the classroom. Unaware of school being a requirement or the legal implications if he continued to not attend, Raphaele began to steal from prosperous neighborhoods as he did not have food at home or lacked other resources (Johnson).

Raphaele’s childhood was drastically altered once he was taken away from his family on April 6 of 1925 and placed in the New York Catholic Protectory, where orphans and juvenile delinquents were committed, at the age of 9 years old for committing petty crimes. It became a recurring theme in Raphaeles life as he would be released to his parents on December 12 of that year, only to be readmitted in March of 1927 for a second time and then again in January of 1929 for the last time at the age of 14. Throughout his many admissions in the protectory, Raphaele was given the name of Robbie which some family members had used in giving him the nickname of “Bob.” Raphaele’s dislike of authority grew as he always tested the church, its philosophies, and any regulations imposed on him. The protectory always pegged him as the leader in guiding the mischievous actions of others and as a consequence was punished with whips. Nonetheless, Raphaele’s disagreement with religion did not diminish the ethical awareness he achieved in differentiating between right and wrong. Furthermore, he loved and nurtured a fascination for the atmosphere the church provided, “candles, nice music, nice flowers, nice designs” (Johnson).

Amidst his parents’ separation, Raphaele began to have a positive outlook on his childhood at the age of 16, where he was able to move to a mixed neighborhood of Jewish, Italian, and Irish kids. He stopped attending school and at the age of 15, had secured his first job as an errand boy for an undergarment retailer. However, Ralph’s life along with the lives of many across the world was altered by the severe worldwide economic hardship that classified that moment in time as “The Great Depression.” Raphaele’s activism solidified in witnessing the working-class fight for survival, including his own family (Fasanella and Umberger). In the 1930s, Raphaele joined the Worker’s Alliance and the Young Communist League (YCL), along with his sister Theresa and childhood friend Jim Dura. Raphael was encouraged to return to school by a co-worker and aspiring 22-year-old architecture who attended City College (Johnson). Raphaele went on to attend the New York Workers School in Manhattan and during his time there, he was socially accepted by his teachers and peers. Even though Raphaele could not spell or write, he and his friend Jim sought out to learn as much as possible. While Jim was a traditional learner and absorber of knowledge by the usage of books, Raphaele’s knowledge came from action and with that knowledge, creating change.

Without struggle, there is no reason to live. If you’re not struggling, you don’t deserve to be alive.

—Ralph Fasanella

Good Man Fighting the “Good Fight” (1936-1938)

As Raphaele blossoms into adulthood, he decides to volunteer at the age of 23 for the Spanish Civil War in order to fight fascism under General Francisco Franco’s regime. Raphaele’s determination to go to Spain was rooted in his belief that fascism mirrored the “dark ages” and an oppressive force where there was “no light, no happiness” (Johnson). Raphaele feared the impacts this will have upon the world, further fueling his desires to contribute in any way possible to this social cause. He knocked on someone’s door and expressed his aspiration to travel to Spain and in March of 1937 he boarded the “Ile de France.” Upon his arrival on February 3rd, Marc felt immediately at home in Spain because of his European background. Marc’s prior experience as a truck driver had led him to assume he will be driving tanks, but instead, he went into transport as there wasn’t a demand for it. Marc served the Fist Regiment de Tren (a transport regiment) until he was temporarily assigned to an antiaircraft unit in April of 1938. In the summer of that same year, Raphaele returns to the Regiment de Tren to now be assigned to the artillery unit at the front and encounters a new commissar who he suspected was a fascist double agent (Fasanella and Umberger). After attempts to express his concerns with the International Brigades in ensuring the safety of his peers, Raphaele returns to the United States in June of 1938. Later that year, the Spanish Republic dismisses the entire International Brigade.

I may paint flat, but I don’t think flat.

—Ralph Fasanella

Social Change as a Blank Canvas (1938-1997)

After the Spanish Civil War, Raphaele returned to the United States, where he continued his activism by now organizing labor unions and the newly formed Committee for Industrial Organization (CIO). Raphaele’s activism included but was not limited to: The International Brotherhood of Teamsters in New Jersey, the Bookkeepers and Stenographers Union in New York, and the United Electrical, Radion and Machine Workers of America (UE). In the summer of 1945, Raphaele is vacationing with some friends in New Hampshire where he was encouraged to start drawing after experiencing a more-or-less fidgeting sensation that directed him to engage with something (Fasanella, Marc). In 1946, Ralph was released from the United Electrical, Radion, and Machine Workers of America due to budget cuts. He then goes on to work for his brothers Sabino (Sam) and Nicolo (Nick) gas station in the Bronx, while painting during the night. Ralphs paintings conveyed the realities of many women and men labor workers, union meetings, strikes, sit-ins, among others. Fasanella’s opinionated, leftist-oriented artwork caused him to be blacklisted among art dealers and galleries after WWII during the McCarthy era (“Fasanella, Ralph”). Raphaele and his family were harassed, to a certain degree continue to be, by the FBI. Amidst the instability of being employed, Raphaele had the ceaseless support of his wife Eva who never doubted the impact of his work.

Conclusion

In Raphaele, I see a man who is not your traditional hero, who you will not see in the pages of your history books, or whose statue will decorate public spaces, but whose bravely along that of thousands deserves to be our models in the creation of a more just and fair world. Spain was the opening of Ralph’s growth, and undoubtedly his story has decorated my own. I am forever grateful to Marc and the Fasanella family for reminding me that the act of being a human continues beyond disasters, setbacks, or failures. Raphaele’s trajectory and impact, are exemplary that our beginning should not be measures of our worth and contributions to the world. I am grateful to have learned about a moment in history I did not know I needed and the community I have created along this invisible thread of fighters and their descendants.

Works Cited

“Current Exhibits.” Fasanella, www.fasanella.org/.

Fasanella, Marc, and Leslie Umberger. Ralph Fasanella: Images of Optimism. Pomegranate, 2017.

Fasanella, Marc. Personal Interview. 29 October 2020.

“FASANELLA, Ralph.” SIDBRINT, Universitat De Barcelona,

sidbrint.ub.edu/ca/content/fasanella-ralph-0.

“Fasanella, Ralph.” The Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives, 4 Sept. 2020,

alba-valb.org/volunteers/ralph-fasanella/.

Johnson, Timothy V. “Ralph Fasanella.” Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives Oral History

Collection, 18 Nov. 2017, wp.nyu.edu/albaoh/ralph-fasanella/.

May, Stephen. “Ralph Fasanella’s America.” Antiques And The Arts Weekly, 18 June 2002,

www.antiquesandthearts.com/ralph-fasanellas-america-2/.

“The Ralph Fasanella Collection and Archive at the American Folk Art Museum: American Folk

Art Museum.” The Ralph Fasanella Collection and Archive at the American Folk Art Museum | American

Folk Art Museum, folkartmuseum.org/resources/fasanellacollection/.