Eleni Mattas

Professor Hernandez-Ojeda

HONS 2011J

18 December 2020

The Story of Fredericka “Freddie” Imogene Martin

Personal Statement:

When I first began this semester I assumed this course would be just another history class. I did not expect to gain such a wide perspective of the various events that led up to World War 2. I especially was unaware of the events that transpired in Spain. When I heard about the American volunteers that willingly sacrificed their comfortable lives here in the States to fight overseas, I was inspired. Today, political involvement has been minimized to social media postings and small, diplomatic debates amongst friends and family. In the 1930s, young people picked themselves up and physically went to fight for things they believed. I was especially interested in women’s role in the Spanish Civil War; women like Freddie, who dropped everything to run hospitals abroad and save lives. These women were the backbone of the entire cooperation. Without women like Freddie, the hospitals on the frontline in Spain would not have been as nearly efficient as they were. I got a chance to personally speak with one of Freddie’s relatives. Barbara Martin is Freddie’s cousin (related through their fathers). The two communicated for many years through letters. It was with both Barbara’s article on ALBA’s website and our interview how I was able to learn all about Freddie’s life and her accomplishments. I am honored to have the opportunity to embody her legacy through my writing.

Introduction

Women’s role in the Spanish Civil War may have gone unnoticed and underappreciated back in the day, but stories like Fredericka (Freddie) Imogene Martin’s remind us of how large of an impact women really did have. Women contributed through both hands-on volunteering in Spain and support from the homefront. Freddie was one of the brave American women who traveled across the sea to Spain to fight against fascism. This paper aims to honor Freddie’s contribution to the Spanish Civil War and acknowledge the selfless sacrifice and passion all volunteers acquired.

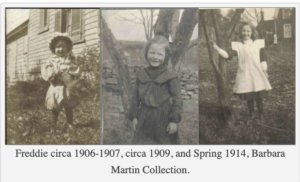

Freddie was born on June 2, 1905 in Cooperstown, NY. Her parents were Lydia C. Pennington and Frederick Alfred Martin. Freddie was very independent and spirited from a young age. After high school, in 1925, she began nursing school at Christ Hospital in Jersey City. She quickly became very successful and driven, earning supervisor positions at various hospitals throughout New York City like Bellevue and Fordham Hospitals. It was clear that although Freddie came from an impoverished background, giving what she could and helping however she could was always her top priority. This was seen not only in her selfless career of nursing, but in the various social justice issues she got involved in throughout her lifetime.

from a young age. After high school, in 1925, she began nursing school at Christ Hospital in Jersey City. She quickly became very successful and driven, earning supervisor positions at various hospitals throughout New York City like Bellevue and Fordham Hospitals. It was clear that although Freddie came from an impoverished background, giving what she could and helping however she could was always her top priority. This was seen not only in her selfless career of nursing, but in the various social justice issues she got involved in throughout her lifetime.

In the early 1930s, Freddie got involved in the nurse’s union. It was at this point that she started taking classes in political science and various languages, like Russian. She married Alexander Cohen and in 1935 traveled to Europe to visit her in-laws. It was on this trip where Freddie became aware of the growing threat that was fascism (ALBA.001).

Freddie’s Journey to Spain

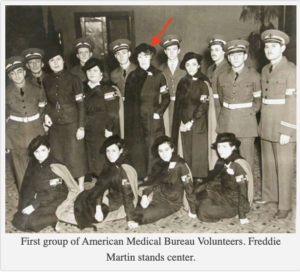

Upon her return, Freddie got involved in the Medical Bureau to Aid Spanish Democracy. This group raised funds and gathered supplies to be sent over to assist the fight against fascim in Spain. During her involvement in this group she even assisted in the design plans for setting up hospitals and uniforms that would be used in Spain. By late 1936 the Medical Bureau began recruiting personnel to send to Spain. Freddie was personally selected by Dr. Edward K Barsky, the head of the Medical Bureau, to join the volunteer team. She was chosen for her leadership and organizational skills; she even “planned a fifty-be d hospital, designed uniforms, gathered and helped to pack supplies of all kinds” (Martin 18).

d hospital, designed uniforms, gathered and helped to pack supplies of all kinds” (Martin 18).

Freddie was originally stationed in El Romeral in the (Province of Toledo) in February of 1937. She served as a nurse treating both wounded soldiers and civilians. Shortly after her and other American volunteers opened an American Base Hospital in Villa Paz. Here, Freddie worked to train nearly 400 local girls as assistants and eventual nurses. In Barbara Martin’s article Freddie described the conditions of her work. She said, “Iodine and alcohol were in short supply and sterilization of surgical instruments was a challenge. When the soap ran out, they made soap. When there were no kitchens in the hospitals, cooking was done over open fires” (Martin 24). It is evident that being a nurse during this war was not a smooth ride by any stretch of the means. Although supplies were minimal and conditions were horrendous, Freddie, along with all the other nurses, doctors, and medical assistants, continued to serve the wounded and ill.

Fredericka’s role was so great where she contributed to between six and nine hospitals and two mobile operating units. Naturally, Freddie achieved the title of Head Nurse. Along with the endless logistics of running these facilities, Freddie had to bear the tremendous emotional turmoil and trauma that came along with her work and erupting surrounding environment. Barbara wrote she had to “solve problems like who would be assigned to burn the dead bodies” (27). Despite the obvious hardships of being a nurse during the war, Freddie was known for keeping spirits high and constantly encouraging everyone around her. “She gained the name of ‘Ma’ for the way she treated both the staff and patients,” Barbara wrote (28).

In late January 1938, Freddie returned to the United States to raise funds for the volunteers left in Spain. As discussed in our class, the Roosevelt administration was very reluctant to give any source of federal assistance to Spain during Franco’s takeover. FDR demanded the U.S. practice a policy of isolation and non-intervention. It was because of this volunteers like Freddie had to take to the streets themselves. Protests, rallies, and donation drives were the key to keeping American volunteers afloat in Spain. Freddie’s fundraising tour took her across the entire country! She gave speeches and conducted interviews spreading the first-hand stories of the volunteers that were on the Republican frontline in Spain (Martin 34). Bombings were the main feature of these stories; numerous close calls and miraculous saves inspired folks to open their pockets and get involved.

Life After the War:

Although the war against fascism abroad was nowhere near ending, in 1939, the efforts in Spain were coming to and end. Nearly all parts of Spain had fallen to Franco’s fascist regime. Freddie was very disappointed and angry at this defeat, however she was not done finding causes to get involved with and helping people. She remarried in 1940 to a Dr. Samuel Berenberg, the Director of Public Health in Greenbelt. One year later Sam received an opportunity from the Department of Interior, Fish and Wildlife to relocate to St. Paul, Alaska.

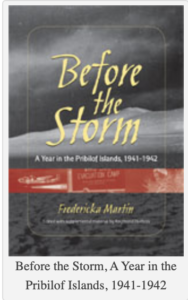

Upon this move Freddie became instantaneously moved by the locals, known as Aleuts. For some reason these individuals were looked down upon. Barbara wrote, “The Aleuts were considered to be dirty, lazy, and uneducated people” (46). It was typical for people to not associate with these natives, but Freddie would not oblige to such a standard. Freddie became so fascinated by the Aleutian Natives she wr ote and successfully published several books about her experience. Freddie relates in her first book, Hunting the Silver Fleece, that living amongst the Aleuts was irresistible compared to their pastime of searching for artifacts of long dead Native Americans on the Maryland shore” (Martin 40). She also published, Before the Storm: A Year in the Pribilof Islands and updated her first book to Sea Bears: The Story of the Fur Seal. Similarly, Freddie assisted in the compilation of an official Dictionary of the Aleut Language. Nonetheless, it is clear that Freddie had numerous fulfilling experiences on St. Paul Island that would influence the rest of her life.

ote and successfully published several books about her experience. Freddie relates in her first book, Hunting the Silver Fleece, that living amongst the Aleuts was irresistible compared to their pastime of searching for artifacts of long dead Native Americans on the Maryland shore” (Martin 40). She also published, Before the Storm: A Year in the Pribilof Islands and updated her first book to Sea Bears: The Story of the Fur Seal. Similarly, Freddie assisted in the compilation of an official Dictionary of the Aleut Language. Nonetheless, it is clear that Freddie had numerous fulfilling experiences on St. Paul Island that would influence the rest of her life.

Freddie became so invested in learning about the Aleuts, she even helped them fight for federal support for food, supplies, and housing for sealers and their families (Marin 60). Both Freddie and Sam worked hard to advocate for the locals to receive the justice and equality they deserved. They even testified before a subcommittee against legislation that was proposed to reduce federal support of the Islands. Freddie’s work towards justice for the disadvantaged Aleutian Natives lines up with her selflessness to assist the disadvantaged Spaniards during the Civil War.

In June of 1942, the Japanese attempted to invade Alaska as World War 2 continued and the fascists attempted to expand in all directions. They began with a bombing of Dutch Harbor and soon invaded the Aleutian Islands, where Freddie and her family were. Fortunately, they were never physically harmed However, Freddie experienced intense post traumatic stress in result of the bombings and invasion. She was brought back to the frightening and vulnerable time she spent in Spain. Similarly, she felt even more worried because she was newly a mother to sweet Tobyanne Berenberg Martin; (named after Toby Jensky and Anne Taft, two nursing colleagues and dear friends of Freddie who served with her in Spain)!

Shortly after Tobyanne’s birth, Sam’s work in Alaska was officially terminated and the family moved back to New York City. Unfortunately Freddie and Sr. Sam Berenberg divorced in 1950. After the tough divorce, Freddie took 9 year-old Tobyanne to Mexico on a trip to decompress and reorient their life. They found themselves liking Mexico so much that they decided to stay and make the permanent move.

A deciding factor for their move was the increasing persecution of suspected Communists by the FBI. Many volunteers from the Brigade “came under scrutiny because they had been or had worked alongside the Communists during the Spanish Civil War” (Martin 65). Dr. Barsky, the Head of the Medical Bureau who initially asked Freddie to go to Spain, even lost his medical license and spent time in prison due to uncooperative behavior with Congressional Investigations. Freddie mentioned a story in one of her letters with her cousin, Barbara about her experience going back to the states to visit her dear friend, Anne Taft. She mentioned that when in Taft’s apartment in NYC, her and Tobyanne felt like they were being watched. A professional gentleman even came to the door in an attempt to question the ladies and their potential involvement with the Communist Party. This was very frustrating and infuriating for Freddie because she was hardly a threat by any means. She was more like a hero who literally saved people’s lives. The pressure from the FBI was continuous for many volunteers post-war and in many cases crossed a boundary becoming very invasive and disrespectful.

Throughout the 60s in Mexico, Freddie and Tobyanne joined and ex-patriot community in Cuernavaca. Freddie continued to write; she added to her writings about the Aleuts and also contributed to Mexican tour books and books on c onversational Spanish. She also began to collect information for a book about the Medical Brigade in the Spanish Civil War. “Freddie believed that there was a need for books about American volunteers” (Martin 69). Freddie felt that the contributions of the Medical Bureau and all of the medical personnel went overlooked and underappreciated. “When Spanish Civil War combat veteran Arthur Landis published The Abraham Lincoln Brigadein 1967, Martin protested the lack of coverage given to the medical units and resolved to write a separate history on the Medical Bureau volunteers” (The Tamiment Library).

onversational Spanish. She also began to collect information for a book about the Medical Brigade in the Spanish Civil War. “Freddie believed that there was a need for books about American volunteers” (Martin 69). Freddie felt that the contributions of the Medical Bureau and all of the medical personnel went overlooked and underappreciated. “When Spanish Civil War combat veteran Arthur Landis published The Abraham Lincoln Brigadein 1967, Martin protested the lack of coverage given to the medical units and resolved to write a separate history on the Medical Bureau volunteers” (The Tamiment Library).

Her work with the Aleuts continued where she even received a grant to research historical records of the Spanish explorations of Alaska. Freddie traveled back to Spain in 1972 for this new project. On her trip she was able to revisit old hospital locations from her time serving as a nurse in the Spanish Civil War. This trip reignited her deep passion and excitement about the work she and others from the Medical Brigade took part in. She set out a goal to document all they had accomplished, however she never finished or published an official book of her writings. She did document a lot of her memories and experiences in journals and in letters to her family, like her dear cousin Barbara.

Freddie became one of seven people awarded with honorary doctorates from the University of Alaska. This award was chosen based on “their leadership roles in the governmental, humanitarian and scientific worlds; both Alaskans and non-Alaskans have been selected for this distinguished honor” (Martin 73).

As time went on, it was difficult for Freddie to continue her advocacy work and writings. She also struggled with illnesses such as, osteoarthritis and tenosynovitis, which affected her ability to walk. Freddie was very proud of her daughter and grandson. Tobyanne went on to become a Professor at the National Autonomous University of Mexico teaching geography. Freddie passed away on October 4, 1992. Her epitaph reads: “FREDERICKA I. MARTIN, June 2, 1905-Oc tober 4, 1992, An Internationalist who fought for peace in the Spanish Civil War and for the rights of the Aleut People of the Pribilof Islands” (Martin 17).

tober 4, 1992, An Internationalist who fought for peace in the Spanish Civil War and for the rights of the Aleut People of the Pribilof Islands” (Martin 17).

Conclusion:

Freddie Martin left an impact on this world. Her work and generous heart touched many which earned their deep admiration and respect. She left a legacy behind not only for her family, but for both the Republicans in Spain and Aleuts in Alaska. Barbara said that Freddie “felt a deep sense of responsibility for those less fortunate, fighting to right the wrongs she found” (Martin 1). This is evident in her selfless dedication to achieving justice and a better way of life for those disadvantaged. In my interview with Barbara she mentioned that if Freddie were alive today she’d be disappointed in the growing amount of hunger and homelessness in this country. It can be assumed that Freddie firmly believed in equality and peace. Although it feels like the United States is currently far from achieving this, it’s the passion and hands-on work of strong, passionate, and driven individuals like Fredericka Martin that are bringing us closer generation by generation.

Sources:

“Fredericka Martin Papers.” Fredericka Martin Papers Preliminary Inventory, The Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, legacy.lib.utexas.edu/taro/utlac/00526/00526-P.html.

Guide to the Fredericka Martin Papers ALBA.001, The Tamiment Library & Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives , 9 Jan. 2020, dlib.nyu.edu/findingaids/html/tamwag/alba_001/bioghist.html.

Martin, Barbara. “My Cousin Fredericka Imogene Martin.” The Volunteer, The Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives , 29 Dec. 2018, albavolunteer.org/2018/11/my-cousin-fredericka-imogene-martin-by-barbara-martin/.

Martin, Barbara. “Interview with Freddie’s Cousin, Barbara.” 28 Oct. 2020.