Cassidy Kristal-Cohen

HONS2011j

Hunter College-CUNY

Prof. Hernandez-Ojeda

Abraham Osheroff: A life of activism and exuberance

Personal Statement

In my studies of the Spanish Civil War, I frequently found myself making comparisons to what had occurred thirty years later in Nicaragua, during the Sandinista era. The similarities between the two events are striking, and numerous. When I discovered that Abraham Osheroff had fought in the Spanish Civil War during the 1930s, as well as traveled to Nicaragua to build homes during the 1980s— I knew that I wanted to study the progression of his life. Primarily relying on resources from the Tamiment Library archive at NYU, as well as from online publications, I came to understand that Osheroff’s activism expanded far beyond the Spanish Civil War, and Nicaragua. Rather, in seemingly every progressive movement of the 20th century (that he was alive for), Osheroff was present and actively fighting. The more I learned about Osheroff, the more I came to admire, and respect him. In particular, I was drawn to his personal, political philosophy titled “radical humanism”. His articulation of this philosophy has had a lasting impact on how I think about my own political work in terms of lying outside a rigid ideology. Learning about Osheroff’s life has humanized the conflict in Spain, and shown me just how truly exceptional the Abraham Lincoln Brigade volunteers were.

Abstract

In 1936, the traditional forces in Spain attempted to dislodge the Republican administration in power. While the Nationalist military failed to successfully gain control of the government, they did launch the country into a bloody three-year war. Across the Atlantic, young leftists in the United States were galvanized into action. The war in Spain was seen as a fight against Fascist ideology, Nazism, and the aggression of the soon to be Axis powers. The United States government refused to intervene in the conflict, in support of the Republican side. In the face of their government’s inaction, some American activists took the situation into their own hands.

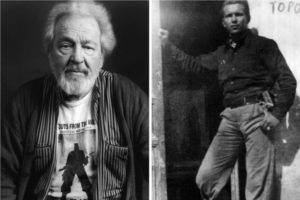

Over the course of the Spanish Civil War, some 3,500 American men and women, who became collectively known as the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, traveled to Spain to aid in the fight against Fascism. One of these immensely courageous individuals was Abraham Osheroff. A carpenter by trade, skilled orator, philosopher, filmmaker and social activist by choice; Osheroff’s journey to Spain marks one instance in a life lived in service to others. By following in the footsteps of Osheroff’s life, one is able to follow the progression of revolutions for social justice and uplift. Through transcriptions of interviews, personal correspondents, and films, it becomes apparent that Osheroff was a radical humanist, a critical thinker and the kind of man whose intelligence and compassion touched the lives of countless individuals.

Abraham Osheroff

Abraham “Abe” Osheroff was born on October 24th, 1915 in Brownsville, Brooklyn. Osheroff’s father worked as a carpenter, and his mother as a low-paid seamstress: both were Russian Jews who had recently immigrated to the United States. Osheroff’s first language was Yiddish, followed by Russian and lastly, English[1]. In the early 1900s, Brownsville was in majority composed of working class Jewish immigrants. Due to this, the community had a strong socialistic consciousness. This consciousness fostered activist tendencies in Osheroff, from an early age. In illustration of this point, Osheroff recounts a memory from twelve years old, in which he joined a Brownsville demonstration in protest of the wrongful death sentence of two Italian radicals, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti (1927). In Osheroff’s own words, growing up in Brownsville was profoundly influential to the person he became as from a young age, “trade unionism, and struggle against injustice was almost like part of my day to day diet”[2].

Osheroff’s participation in community activism continued in his early teens. Osheroff was 14 when the Great Depression hit the United States. Due to its working class composition, Brownsville was severely crippled. Osheroff remembers seeing countless grown men wandering the streets homeless, as well as furniture piled on the curb, left from the homes of the evicted. Brownsville, however, refused to accept the evictions[3]. When families were forced out of their homes, the community helped them move their furniture back in. A group that Osheroff had founded in high school, with the original dual-purpose of weight lifting and listening to classical music, was enlisted in this effort[4]. At age sixteen, Osheroff was arrested for his eviction activism and was badly beaten by the police. Despite opposition, the community campaign to replace furniture was so successful that many landlords found it more profitable to allow tenants to live without paying rent, than to have to pay to have their belongings removed over and over again[5].

At age 16, going on 17, Abraham Osheroff joined the Young Communist League[6]. While he had an aversion to organized political parties, he soon came to the realize that the Communist’s were the only people wiling to truly fight for the rights of the poor and working class. He concluded it was the “only place one could go if one wanted to militate”[7]. Joining the Communist League gave Osheroff a feeling of belonging, and helped him overcome feelings of alienation. In high school, the Communist League became the center of Osheroff’s life, socially, politically, and ideology. Members of the League saw the work they were doing, providing first aid and social assistance to the needy, fighting for a better library, as an arm of a global struggle for equality. They were heartened by the Soviet Union, which they viewed as the end goal of their struggles. For Osheroff, his membership to the Party led to the development of an international-minded political consciousness, as well as a sense of hope for the future[8].

After high school, Osheroff went on to pursue a social science degree from the City College of New York. At CCNY, his activism continued in the form of weekly demonstrations against the City College President who attempted to squelch leftist thought on campus[9]. During his college years, Osheroff remembers reading Mein Kampf and realizing the weight of Hitler’s dictatorship. He recounts a sense that “something very big was unfolding and what we were doing was not satisfactory enough”[10]. While Osheroff was still actively working for the Communist Party during this time, he recounts feelings of powerlessness and desperation to do something of value in the face of Nazism. However, the plausibility of militarily supporting the fight against Hitler never crossed his mind[11].

After college, Osheroff began vocational work as a carpenter, as well as worked for the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). He was tasked with organizing coal workers in Pennsylvania and Ohio[12]. Around this time, war broke out in Spain. The Communist Party immediately began raising funds for Republican troops, as well as mobilizing American volunteers to fight overseas. Once it became clear that Hitler and Mussolini supported the Nationalist forces, Osheroff began to view Spain as a long awaited opportunity to combat fascism. Osheroff had always thought of his “voluntarism” as risky to the point of death, and as a form of militancy. Thus, the idea of traveling to Spain seemed a natural extension of what he had been fighting against his entire life[13]. In the spring of 1937, after seeing newsreel of Guernica being bombed, Osheroff officially enlisted. He stressed that the decision to volunteer in Spain was not solely political; rather it was also an emotional response to the pent-up anger he felt at his own inability to help. For him, it “was the easiest thing to do”[14], “not to go was unbearable, and to go was difficult and dangerous, but I could cope with that”[15].

Abraham Osheroff swam on to the shore of Spain on May 30th, 1937, when an enemy submarine off the coast of Barcelona torpedoed the boat transporting him from France[16]. Fifteen to thirty people were killed in the attack. Osheroff survived without a scratch, and was sent to Tarazona de la Mancha for training[17]. He describes the beginning of the war as “farcical”. By the time he arrived, Osheroff reports that it was very clear the Republicans were losing[18]. Except for a few men, no one in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade had ever had military training or even fired a gun. Training primarily consisted of marching in the hot sun, listening to morale-building speeches, minimally practicing firing and assembling guns, and executing drills[19]. Within the Brigade, Osheroff reports that all racial, ethnic, and sexual distinctions were overcome in the trenches. He illustrates this point by referencing an entirely white unit that was commanded by an African American man named Oliver Lore[20]. While coexisting in the same platoon was historic for blacks and whites, Oliver Lore’s position of power over a white squadron was revolutionary. Osheroff describes his war experience at best, as filled with intense discomfort. The Lincoln Brigade, and most brigades on the Republican side of the Civil War were sorely equipped, and undersupplied. Often times the soldiers went hungry for days, with very little sleep. In Osheroff’s own words:

I don’t think any American combat men were ever so poorly equipped, relative to the enemy, so poorly fed… so poorly taken care of in terms of hospital services, relative to the enemy they fought—as those of us in the Lincoln Brigade. Considering that, rate of defection was minute, I can’t imagine men standing up better under those circumstance[21].

At worst, Abraham Osheroff’s war experience was incredibly dangerous, and plagued with intense fear. He described this fear as all consuming— a fear that he would not survive the war, would never get to experience more than his short life had allowed, a fear that he’d never hold a girl again, or see his mother[22].

For Osheroff, the primary escape from the terror, fear, and discomfort of wartime was the quixotic element of the Republican side. Osheroff explains that since all of the soldiers fighting in the Internationale Brigade wanted to be there, and truly believed in the Republican cause, the soldiers operated on an almost religious level. Osheroff describes the war as a “spiritual…ennobling experience”[23]. The idealistic nature of the soldier’s mission translated into the battlefield: allowing the Lincoln Brigaders to overcome how ill-equipped and underfed they were. Singing songs played a major role in this aspect of the war, as it was effectively used to boost soldier’s morale, transcend pain, and reorient them with the idea of taking part in something larger than themselves[24]. As Osheroff recounts, due to the moralistic component of their service, the Brigadiers never surrendered[25].

During the course of the Spanish Civil War, Osheroff helped take the town of Belchite, fought in the battles of Qinto Lochita, and at Fuentes De Ebro. In the latter fight, in 1938, he was injured when machine gun fire tore through his knee. In August, he was sent home[26]. Spain falling in August 1939 was deeply painful for Osheroff, who felt he had emotionally stayed in the war until it ended; however, the loss did not come in the shock. For Osheroff, the inevitability of losing was a constant thought, however he had to falsely convince himself otherwise in order to survive. While the wound of Spain closed eventually, the loss still remains as a “livid scar” that painfully comes alive when touched[27].

The largest effect that fighting in Spain had on Osheroff’s life was the way in which it altered his perception of the world. He describes his time in Spain as an emotional peak that continually emerged him in feelings of togetherness and deep love. Fighting in Spain taught him of the “enormous potential for caring and loving”[28]. Everywhere he went Spaniards opened their homes, and hearts to him. He reports feeling closer to the Spaniards than to his own siblings[29]. Further, when Osheroff enlisted, he was a naïve 22-year-old kid. When he arrived home, he was a seasoned military and political veteran. His illusions that the fight with goodness and justice on its side would ultimately preserver, was utterly shattered—leaving Osheroff with a more pessimistic, and pragmatic view of political conflicts[30].

After returning to the United States, Abraham Osheroff’s sense of military and political duty did not wane. He was very active in the Communist Party, before he enlisted in World War II in 1941. He saw WWII as an extension of fighting in Spain, but with more favorable conditions. He participated in the invasion of Normandy, after D-Day had already occurred, and became a Sergeant of the 77th Pacific division[31]. When Osheroff returned from WWII, McCarthyism had begun to plague the United States. In 1949, eleven members of the Communist Party were arrested. After being tipped off by a friend within the Justice Department, that he was going to be in the next wave of arrests— Osheroff went into hiding[32]. During this time, he did not see his family or friends. He worked odd jobs, and changed his identity, location, and social security number every six months to evade the FBI’s grasp[33]. By the time Osheroff came out of hiding in 1953, he had undergone a “crisis of conviction” in terms of his involvement in the Communist Party[34].

Osheroff became suspicious of Communism, due to Stalin’s human rights abuses (as exemplified by his suppression of the Hungarian revolution), as well as because of rumors that the US Communist Party had mismanaged its funds[35]. He officially left the Party in 1956. He was ostracized for this decision, and forced to cut ties with most of his associates, close friends, and the only community he had ever known. Osheroff moved to California shortly after, dropped out of politics, and began working as a carpenter again[36].

During the Civil Rights Movement, Osheroff became politically re-engaged. He helped fund raise for the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC)[37]. After raising $20,000 for his venture, Osheroff spent a year in Mileston, Mississippi, building a community center, and helping locals’ register to vote. Mileston was one of the poorest black neighborhoods in the nation, at the time. Osheroff reports, he was the only white person in the area for 14 miles[38]. In the mid-1960s, Osheroff became involved in the fight against real estate agents in Venice Beach, who were displacing the local population in their redevelopment efforts[39].

In 1970, Osheroff returned to Spain for the first time after the War, and equated it with a religious experience. Upon his return, he decided to make a documentary about the United States’ support of Franco’s regime and his experience during the War, titled Dreams and Nightmares[40]. Released in 1974, the film won several prizes in Europe. Due to its acclaim, Osheroff was offered countless speaking engagements, as well as a job teaching a course on the Spanish Civil War at the University of California in Los Angeles[41].

In 1985, Osheroff had stopped teaching, and raised over $45,000 to fund a trip to Nicaragua[42]. At the time, the Reagan administration was funding and training counter-revolutionaries who were trying to overthrow the Nicaraguan left-wing Sandinista government. Osheroff was starkly opposed to this intervention. Thus, for a year, Osheroff, his two sons, and a crew of six volunteers used the funds they had raised to build houses in a small Nicaraguan community[43]. Osheroff launched this initiative firstly, to help rebuild neglected infrastructure, and secondly, to show the Nicaraguan people that there were Americans who supported them, and opposed Reagan’s militant policies. He reminisced on his trip, stating, “It was the most positive and rewarding experience of my life”[44].

In 1989, Osheroff moved to Seattle with his second wife, where he was offered a teaching position at the University of Washington[45]. In 2000, he directed a second documentary film titled The Volunteer, about the usage of posters during the Spanish Civil War[46]. In the early 2000s, while teaching at the college, Osheroff participated in rallies against the Iraq War, and US militarism and repression around the globe[47]. Around this same time, his lifetime of activity began to catch up with him. As his health deteriorated, he was forced to undergo two heart operations, and three spinal surgeries. On April 6th, 2008, Abe Osheroff passed away at age 92. He left behind his wife Gunnel, and six, now adult, children[48].

In one of the last interviews before his death, Osheroff stated, “not to react to the injustices of the world is to live something less than a fully human life”[49]. Abraham Osheroff truly lived by this principle. This is attested to by the fact that the path of his life can be used as a roadmap for movements of equality that took place in the United States, over ninety years. At age 15, during the Great Depression, Osheroff fought against evictions. During the Civil Rights movement, he helped register poor blacks to vote in Mississippi. During the 1980s, he built homes for the impoverished Nicaraguans. He fought, passionately, against the Vietnam War, the Iraq War, gentrification, and fascism in all its forms. He fought for the downtrodden, the disenfranchised, and the voiceless.

While fighting alongside the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War may be the cause he is best known for, it was not the first or last “good fight” he participated in. Rather, due to his lifetime of relentlessly and passionately fighting for justice, Abraham Osheroff can be considered a true American hero.

Works Cited

[1] The Good Fight: The Abraham Lincoln Brigade in the Spanish Civil War: Production Materials, Series II: Interview Transcripts; ALBA.216; Box 1; Folder 55; Tamiment Library/Robert F. Wagner Archives, New York University

[2] The Good Fight: The Abraham Lincoln Brigade in the Spanish Civil War: Production Materials.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Seattle Pi, “From Spanish Civil War to Iraq War”, Gregory Roberts, January 13 2004; ALBA.VF.002; Box 6; Folder 88; Tamiment Library/Robert F. Wagner Archives, New York University.

[5] John Gerassi Papers, Series I: Oral History Transcripts; ALBA.018; Box 6; Folder 2; Tamiment Library/Robert F. Wagner Archives, New York University.

[6] Ibid.

[7] The Good Fight: The Abraham Lincoln Brigade in the Spanish Civil War: Production Materials.

[8] Ibid.

[9] New York Times, “Abe Osheroff, 92, Veteran of Abraham Lincoln Brigade”, Douglas Martin. April 13, 2008.

[10] The Good Fight: The Abraham Lincoln Brigade in the Spanish Civil War: Production Materials.

[11] Ibid.

[12] John Gerassi Papers.

[13] The Good Fight: The Abraham Lincoln Brigade in the Spanish Civil War: Production Material.

[14] Ibid.

[15] John Gerassi Papers.

[16] Seattle Pi, “From Spanish Civil War to Iraq War”.

[17] John Gerassi Papers.

[18] Ibid.

[19] The Good Fight: The Abraham Lincoln Brigade in the Spanish Civil War: Production Materials.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid.

[22] The Good Fight: The Abraham Lincoln Brigade in the Spanish Civil War: Production Material.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid.

[26] The Volunteer, September 2005; ALBA.VF.002; Box 6; Folder 88; Tamiment Library/Robert F. Wagner Archives, New York University.

[27] The Good Fight: The Abraham Lincoln Brigade in the Spanish Civil War: Production Materials.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Seattle Pi, “From Spanish Civil War to Iraq War”.

[32] Ibid.

[33] John Gerassi Papers.

[34] Seattle Pi, “From Spanish Civil War to Iraq War”.

[35] Ibid.

[36] John Gerassi Papers.

[37] The Volunteer, September, 2005.

[38] John Gerassi Papers.

[39] Ibid.

[40] New York Times, “Abe Osheroff, 92, veteran of Abraham Lincoln Brigade”, Douglas Martin, April 13, 2008.

[41]Ibid.

[42] New York Times, “Old Warrior Now on Road to Nicaragua”, Virginia Escalante; ALBA.VF.002; Box 6; Folder 88; Tamiment Library/Robert F. Wagner Archives, New York University.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Letter to Ed Lending; ALBA.068; Box 1; Folder 19: Tamimet Library/Robert F. Wagner Archives, New York University.

[45] Seattle Pi, “From Spanish Civil War to Iraq War”.

[46] New York Times, “Abe Osheroff, 92, veteran of Abraham Lincoln Brigade”.

[47] Seattle Pi, “From Spanish Civil War to Iraq War”.

[48] The Volunteer, “Added to Memory’s Roster: Abe Osheroff”, March 2008; ALBA.VF.002; Box 6; Folder 88; Tamiment Library/Robert F. Wagner Archives, New York University

[49] New York Times, “Old Warrior Now on Road to Nicaragua”, Virginia Escalante; ALBA.VF.002; Box 6; Folder 88; Tamiment Library/Robert F. Wagner Archives, New York University.