Mei Meadow

HONS 2011J

Final Essay

Professor Maria Hernández-Ojeda

Vincent Lossowski

Personal Statement

While researching the life and involvement of Vincent Lossowski in the Spanish Civil War, I initially came upon several interesting facts about his numerous military services and affiliation with the Communist Party online; however, it was only when I interviewed Paul Lossowski, Vincent Lossowski’s son, and read more personal artifacts such as letters between him and his mother and wife during his time in Spain that I achieved a better understanding of who Vincent Lossowski was. More formal correspondences and newspaper clippings from after the war documented the harassment by the U.S. government that Lossowski experienced for serving as a volunteer in Spain. I began to contextualize the facts with historical and societal influences during his life as well as familial anecdotes to piece together an interpretation of his life and experiences in the Spanish Civil War.

Although I had access to some of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives, a majority of the documents with quotes and interviews with Vincent were not digital and, due to COVID-19, were inaccessible. A major contribution to my writing process was an original copy of the local upstate NY magazine from 1983, Sunday Democrat and Chronicle, which was generously sent to me by Paul Lossowski. The newspaper contained an article about Vincent that quoted him directly. The article details how Vincent and other young men in Rochester became involved in the Spanish Civil War as well as their experiences of the war. Although online biographies helped chronologize Vincent’s military whereabouts, reading quotes from and about other upstate volunteer veterans who were part of Vincent’s community taught me more about his character due to the contrast between what he chose to write home and speak about later in life and military records. This helped me create a more well-rounded view of Vincent Lossowski’s experience in the Spanish Civil War.

The Story of Vincent Lossowski (1913-1984)

Life before the Spanish Civil War. One year before the assassination of the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo started World War I, Vincent Lossowski was born in a Polish family in Rochester, New York, which is about 250 miles away from New York City. New York became an epicenter for socialist and communist societies and leftist movements that would help shape young Vincent’s life dramatically (“Lossowski, Vincent: Biography”). While Vincent grew toward adolescence from the isolated safety of American soil, the Great War raged on in Europe (1914-1918). By the time Vincent turned 18 years old, Vincent had to step up and help support his working-class mother and sister, Wanda, financially. In March 1932 at the age of 18, Vincent enlisted in the U.S. Army for three years where he rose to the rank of sergeant in the 1st Coastal Artillery Anti-Aircraft Unit at Fort Randolph in the Panama Canal Zone (“Vincent Lossowski (1913)”). During his time in Panama, he would send home his wages to support his family back in Rochester.

Soon after his enlistment in the U.S. Army ended, Vincent worked as a machinist back in his hometown of Rochester. He became an active member of the Young Communist League (“Lossowski, Vincent: Biography”), which appealed to him because of his working-class identity and left-leaning political alignment. Although he would later be disenchanted by communism after watching the inhibition of personal liberties and complications in the Soviet Union and China, young Vincent, like many of his upstate peers, was drawn to communism when the party began organizing unions for working-class people. The Young Communist League (now known as the League of Young Communists USA) was formed in 1920 as an organization affiliated with the Party of Communists USA that fought for democracy, labor rights, women’s equality, racial justice, and peace (Communist Party USA; League of Young Communists USA). Before the Spanish Civil War, there was little societal pressure to hide one’s allegiance with the Communist Party, so Vincent had no trepidation toward becoming a known registered member of the Communist Party.

Involvement in the Spanish Civil War. On July 1936, General Francisco Franco initiated his coup d’état with the military backing of Adolf Hitler against the democratically elected Second Republic of Spain, formally beginning the Spanish Civil War. The German Luftwaffe introduced the bombardment of civilian populations to warfare. Numerous newsreels were created during this time to document and inform the public of what was happening in Spain. On a Spring night in 1937, one of these newsreels depicting the atrocities committed in Madrid was shown in a movie theater in New York and was seen by 23-year old Vincent. In an interview with a local newspaper, Lossowski recalled seeing the fascists not only destroy buildings but also attack civilians indiscriminately: “you could see people scurrying all over. And you could see the dead people in the street” (Zeigler 8). Although he had only entered the theater to see a feature film that night, Vincent emerged with a lasting impression from the newsreel that would impact the rest of his life.

Like many of the American volunteer veterans, Vincent was appalled by the inaction of the U.S. government whose liberal democratic ideals of separation of church and state, women enfranchisement, and education upheld by the Second Republic were being violently attacked by the fascist forces. Vincent was driven by the strong call to action after seeing the newsreel, so when the topic of the Spanish Civil War inevitably came up at a party, Vincent befriended a Communist organizer from Buffalo who mentioned that the Communist Party was planning an international brigade to go to Spain (Zeigler 8). Since he already had military training, Vincent believed that he could be an asset to the Republic, so he joined the International Brigades and sailed to France on the S.S. Berengaria steamship in July 1937.

Many of Vincent’s local community members in Rochester supported the Spanish Republic but refrained from going to Spain. Instead, they chose to show their support through fundraising as opposed to engaging in combat. Despite having a safer alternative, Vincent, like many other volunteers, was led by his gut reaction to do what he believed was right, even if that meant putting himself in harm’s way. However, Vincent didn’t know how to break the news to his mother that he wanted to leave for Spain. As his mother’s only son, Vincent knew that if his mom was aware of his plan to go to Spain, she would never allow it. Instead of telling her outright, Vincent conceived a plan to mislead his mom about his whereabouts. While he told his sister the truth, Vincent told his mother that he was leaving to visit a friend in California, which would explain his long absence from home. He gave the friend a bundle of prewritten letters addressed to his family in Rochester and arranged for them to be sent regularly back home as if he was enjoying the coast along the Pacific rather than being on the front lines of another country’s civil war across the Atlantic (Zeigler 8; Paul Lossowski). Soon after his departure, his mother found out that her son was in Spain, but at that point, it was too late to retrieve him.

Upon his arrival in France, Vincent learned that his deception had been unsuccessful. Once exposed, Vincent wrote a letter to his mother and sister explaining that he was not driven to volunteer “out of the desire as foolish as romantic adventure, but with a sound determination to do [his] little bit that working people may live like human beings instead of like slaves under the rule of fascism” (Letter to Mom and Wanda, July 1937). After composing the letter, Vincent among other international volunteers crossed into Spain over the Pyrenees mountains on foot. From the time he set foot in Spain until the Republic withdrew the International Brigades in September 1938, Vincent served with the Abraham Lincoln Brigade as a battalion observer, artillery firing officer, and attained the rank of lieutenant (“Lossowski, Vincent: Biography”).

Soon after his arrival, 24-year-old Vincent, among many other young American volunteers, took part in the infamous Battles of Quinto and Belchite. Both battles destroyed the local landscape, architecture, and civilian life. In Zeigler’s newspaper article, Vincent recalls fighting with his fellow soldier, Harry Rubens, house-to-house in the battle of Quinto:

Harry Rubens and I were flushing out houses, and we broke into this doorway and there was an old man, an old woman, a younger woman and her children. The old man and the old woman fell to their knees – they called us los rojos, ‘the Reds’ – and the women were fearful they were going to get raped. Harry reached into his knapsack and got out some bread and gave it to them. The old woman hugged his knees in joy and he lost his balance and fell out into the street and was shot by a machinegun. [Rubens survived]. (14-15)

One can only imagine the swirl of emotions in young Vincent’s mind as he fought for the Spanish people despite the exorbitant fear they expressed toward him. However, this act of kindness he and Rubens showed them exhibits many of the Lincoln Brigade volunteers’ benevolent objective: to do the right thing.

The Battle of Belchite began at the end of August, lasted two weeks, and the village remained under Republican control until it was retaken by the Nationalist forces in 1938 (Ciaccio, et al.). Mere weeks after he arrived in Spain, Vincent was thrown into a battle directly on the front where his odds of survival were very slim. When the battle began, the Lincoln Battalion was 540 men strong; 10 days later, only 70 soldiers remained (Zeigler 14). Miraculously, Vincent survived – but he did not emerge unscathed. A ricocheting bullet struck his left leg and prevented him from returning to the battlefront for the rest of September, October, and into November of 1937 (“Spanish Civil War Veteran Fights again”). During his convalescence in a hospital at Benicàssim, he wrote home to his mother and sister. Although they now knew that he was in Spain, Vincent omitted the fact that he had been wounded in battle and continued to write home that he was “way behind the lines and ridiculously safe” (Letter to Mom and Wanda, 16 Oct. 1937). Contrary to his letters home, it is documented that Vincent was very much on the front lines: “he commanded an Anti-Tank battery and later a mountain artillery unit, utilizing guerilla tactics” (Proctor, “Memorandum”).

Instead of writing home about his dangerous predicament, Vincent spent his letters marveling at the values of the Republic he was fighting for:

Under the liberal “Peoples Front Government” the people are quickly learning the advantages of modern agriculture and in a country of people where almost 50% of the population can’t either read or write, the government is building modern schools, which adults may attend, and the attendance is remarkable. After the war with the Loyalist Government [is] victorious, the country will advance agriculturally, industrially, and culturally by leaps and bounds. (Letter to Mom and Wanda, 16 Oct. 1937)

Perhaps he focused on the ideals of the Republic rather than his injuries with the recipients of his letters in mind to avoid worrying his mother and sister, to give them hope, or to help them understand what he was fighting for. Maybe this was a demonstration of Vincent’s bravery as a soldier, or Vincent’s composition about the Republic helped give him strength by reminding him what he was fighting for. Whatever his intentions were, Vincent managed the strength to fully recover and return to the fight for yet another infamous battle –the Teruel Offensive.

In January 1938, the Republican forces desperately tried to fight off the Nationalist troops at Teruel. Through subzero temperatures, the Republicans struggled to hold onto Teruel, even with the help of their international brigades. Among the volunteers were Lossowski, Douglas Male, whom Vincent was photographed with during his hospital stay in the Fall, and another young man from Rochester by the name of Johnny Field. Of the three men, only Lossowski survived. Zeigler describes the Teruel Offensive as “one of the fiercest battles of the war” (10). Field was killed in battle while heroically providing cover for other Republican forces to retreat, and for this act, 45 years later Vincent would say, “Johnny Field was the first Rochester man killed in World War II.” Like many Lincoln Brigade veterans, Vincent considered the Spanish Civil War as the beginning of World War II (Zeigler 15).

In addition to these losses, Vincent and the surviving members of the Republican forces were running low on supplies but clung to the Teruel train station to be connected to Valencia. A bleak photograph shows the conditions Vincent endured for a few cold weeks (see fig. 1): huddled masses and scant and strewn about supplies under makeshift shelters using whatever structures of the war-torn area remained. Although Vincent continued to fight in Spain until all of the International Brigade troops were withdrawn, a majority of his remaining military experience in Spain was comprised of retreat after retreat. However, after the war, Vincent was identified as a member of the “Sons of the Night” – a renowned guerilla Loyalist group which “dynamited bridges, railroad mined roads, cut communication lines, pied, sabotaged, and spread terror wherever they struck” (Dixon). Another newspaper clipping states that the group’s claim to fame was storming and successfully releasing 300 Republican prisoners of war behind enemy lines (“Guerilla in Spain Now Fights for U.S.”). Although the latter part of his time in Spain was mostly spent retreating, Vincent’s sacrifices, skills, and bravery indispensably helped fend off fascism and bought the world time to gear up for the official beginning of World War II.

In September 1938, the International Brigades were pulled back to Barcelona and formally withdrawn by the Republic forces in a futile attempt to negotiate peace with the Nationalists, but Vincent felt like his work in Spain was not complete. Even after risking his life countless times for the cause, Vincent tried to voluntarily stay behind in Spain to help defend Barcelona with a fellow Rochester volunteer, Jack Shulman; however, both were rejected and forced to board a train and return to upstate New York in January 1939. In preparation for his arrival, he wrote his last and longest letter yet to his mother and Wanda notifying them that he regrets he wouldn’t be able to join them for Christmas that year and prepared them for the man who would be returning to Rochester in a matter of weeks (Letter to Mom and Wanda, 6 Dec. 1938). The letter also acts as Vincent’s farewell to Spain and as a vessel in which he remembers his fallen soldiers. He knew perfectly well that without the International Brigades, the Nationalists were going to win and the battle against fascism would continue. When he and Shulman returned to Rochester’s New York Central Train Station on February 7th, 1939, over four hundred people came to greet them. Despite the celebrations (Zeigler 15), in Vincent’s mind, the Spanish Civil War was merely a battle in the ultimate war against fascism; while he lamented losing the battle, he returned to Rochester determined to be prepared to win the war.

Life after the Spanish Civil War. Back in the U.S., Vincent continued his professional career as a machinist and worked at the Brundy Engineering plant in the Bronx. He upheld his strong morals for the fair and good treatment of working-class people by participating in a United Electrical, Radio, and Machine Workers strike seven months after he came home from Spain (“Lossowski, Vincent: Biography”). Although the U.S. formally exited its isolationist mindset and became involved in World War II and the fight against fascism, the American volunteers who had gone to Spain only about five years prior were seen by the U.S. government as “premature anti-fascists.” Despite the scrutiny, Vincent kept at his military career: he joined the Coast Guard and persisted with his fight against fascism by serving once again as a captain in the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) unit in North Africa during World War II. For his service in the OSS, Vincent was awarded the Army’s Legion of Merit (Zeigler 13). When World War II ended, Vincent returned to Rochester as a captain and a decorated war hero from four separate services at the age of 32. Once back in the states, he decided to finally settle down and start a family. He met and married his wife Helen and raised three children, but his service during the Spanish Civil War would come back to haunt him.

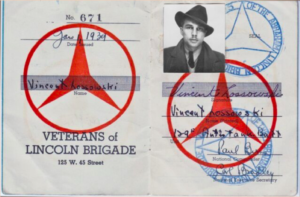

Due to the Russian aid given to the Republic during the Spanish Civil War, many of the volunteers were investigated by the Congressional Military Affairs Subcommittee in the 1950s and deemed communists and anti-American. Vincent was no exception. Even though he had a well-documented, outstanding military career with numerous commendations for bravery and service to his country, his record as a member of the Young Communist League as a young man and ongoing association with the Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade (VALB) (see fig. 2), which was deemed a Communist-front organization by the Subversive Activities Control Board, made him a target during the infamous McCarthy era in the U.S. (“Lossowski, Vincent: Biography”).

During the trial, Vincent’s impressive military record supported his case that his actions in Spain did not prove that he was anti-American, rather they showed that he was an exemplary American soldier. Newspaper clippings and numerous reports document Vincent’s multiple military services with the U.S. When accused of having communist ties, Major General William J Donovan, director of the Office of Strategic Services issued a statement to Vincent’s defense, praising Lossowski for serving “with a character rating of excellent and an efficiency rating of superior” (“Subcommittee Gives Out Names of 16 Whose Past ‘Reflects Communism,’ Says Counsel, 19 July 1945). While a successful trial got the government agencies off Lossowski’s back, his family still received a few mysterious visits from unidentified persons, who were presumably trying to investigate his communist ties (Zeigler 13). Due to his activities in Spain and U.S. anti-Communism sentiment, Vincent also had little job stability, but he didn’t let this discourage him nor his children from standing up for what they believed was right (Lossowski, Paul).

For the rest of his life, Vincent grappled with and shared his experiences in Spain. He granted numerous interviews, gave lectures at local colleges, and often spoke of his war experiences with his children to pass along a piece of history that is too often overlooked in American education. Despite the harassment he endured, Vincent’s core values to look out for his fellow humans internationally and domestically persisted until the end of his life and is carried on by his children. Undeterred by ever-present risks of incarceration and the endless barrage of threats levied by the McCarthy-era, Vincent led by example to stand up for what he believed in by taking his family to protests, speaking openly about his experiences in the war, engendering an aura of caring acceptance for all people in the world, and keeping left-leaning coffee table reads and coloring books in the house for his children (Lossowski, Paul). In addition to these acts of spiritual resistance, Vincent proudly remained an active member of the Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade until he passed away in 1984 (“Lossowski, Vincent: Biography”).

Conclusion

The dangerous and daunting act of going to Spain for Vincent Lossowski was so instinctual, that it took him almost his entire lifetime to figure out exactly why he went to Spain (Zeigler 8). Due to Vincent’s strong moral compass and sense of self, he immediately identified fascism as a demon that defied his core beliefs; therefore, the decision to fight against fascism felt predetermined. It was simply the right thing to do. Perhaps by clandestine happenstance or in the interesting, magical way life plays out, Vincent walked into the theater in 1937 and chanced upon the newsreel that would impact the rest of his life. His sacrifice, bravery, and experience in the Spanish Civil War are parts of his legacy, so to uphold his memory and learn about this key point in history, we need to remember his story.

Works Cited

“About Us.” Communist Party USA: People and Planet Before Profits, https://cpusa.org/about-us/. Accessed 28 Nov. 2020.

“About Us.” League of Young Communists USA, https://leagueofyoungcommunistsusa.org/ about/. Accessed 28 Nov. 2020.

Angus, Caroline. “Tag: Battle of Teruel: This Week in Spanish Civil War History – Weeks 77-81: Teruel and Cáceres, January 1938.” Caroline Angus – New Zealand author and historian. Thomas Cromwell and Tudor expert. Spanish history, culture, civil war, and historical memory writer, WordPress.com, 4 Dec. 2017, https://carolineangusbaker.com/ tag/battle-of-teruel/. Accessed 18 Nov. 2020.

Ciaccio, Nichali, et al. “The Ruins of Belchite.” Atlas Obscura. https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/the-ruins-of-belchite-belchite-spain. Accessed 27 Nov. 2020.

Dixon, Kenneth L. “Guerilla Guerilla Chief: Blue-bearded Brooklynite is Showing Italians New Tricks.” Unspecified Newspaper. Undated. Box 1, Folder 13. ALBA.216 The Good Fight: The Abraham Lincoln Brigade in the Spanish Civil War: Production Materials; Series I: Background Files; Lossowski, Vincent. Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives. Elmer Holmes Bobst Library, 70 Washington Square South, New York, NY 10012, New York University Libraries.

“Guerilla in Spain Now Fights for U.S.” Undated. Box 1, Folder 13. ALBA.216 The Good Fight: The Abraham Lincoln Brigade in the Spanish Civil War: Production Materials; Series I: Background Files; Lossowski, Vincent. Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives. Elmer Holmes Bobst Library, 70 Washington Square South, New York, NY 10012, New York University Libraries.

Lossowski, Paul. Personal Interview. 9 November 2020.

“Lossowski, Vincent: Biography.” The Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archive, https://alba-valb.org/volunteers/vincent-lossowski/. Accessed 10 October 2020.

Lossowski, Vincent. Letter to Mom and Wanda. July 1937. Box 1, Folder 1. ALBA.071 Vincent Lossowski Papers; Series I: Correspondence. Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives. Elmer Holmes Bobst Library, 70 Washington Square South, New York, NY 10012, New York University Libraries.

Lossowski, Vincent. Letter to Mom and Wanda. 16 Oct. 1937. Box 1, Folder 2. ALBA.071 Vincent Lossowski Papers; Series I: Correspondence. Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives. Elmer Holmes Bobst Library, 70 Washington Square South, New York, NY 10012, New York University Libraries.

Lossowski, Vincent. Letter to Mom and Wanda. 6 Dec. 1938. Box 1, Folder 2. ALBA.071 Vincent Lossowski Papers; Series I: Correspondence. Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives. Elmer Holmes Bobst Library, 70 Washington Square South, New York, NY 10012, New York University Libraries.

Proctor, Clifford M. “Memorandum: 1st. Lt. Vincent Lossowski.” Undated. Box 1, Folder 13. ALBA.216 The Good Fight: The Abraham Lincoln Brigade in the Spanish Civil War: Production Materials; Series I: Background Files; Lossowski, Vincent. Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives. Elmer Holmes Bobst Library, 70 Washington Square South, New York, NY 10012, New York University Libraries.

“Subcommittee Gives Out Names of 16 Whose Past ‘Reflects Communism,’ Says Counsel.” Unspecified Newspaper. 19 July 1945. Box 1, Folder 13. ALBA.216 The Good Fight: The Abraham Lincoln Brigade in the Spanish Civil War: Production Materials; Series I: Background Files; Lossowski, Vincent. Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives. Elmer Holmes Bobst Library, 70 Washington Square South, New York, NY 10012, New York University Libraries.

“Vincent Lossowski (1913)”. Fold3 by ancestry, 23 May 2013, https://www.fold3.com/page/ 623213689-vincent-lossowski-1913. Accessed 10 October 2020.

Zeigler, Michael. “When Americans Fought in Spain.” Democrat and Chronicle, 10 April 1983, pp. 8-15.

Dear Mei,

I am Vincent’s youngest child and only daughter. It was a pleasure to read your article about my father. I agree that his story needs to be remembered and that you have helped that become a reality. I am delighted, as my dad would be, that there are young and intelligent people that have taken the time to recognize the difficult sacrifices that the volunteers made during this time in history. If only our own country assisted the legally elected democracy that my father and others were fighting for then I believe fascism would not have had the strong hold to continue and build its ugly regime in Europe. There are so many frightening similarities between then and now in this country. We have had four years of someone who repeats lies after lies and almost half the population believes the lies over the well documented truths. There is hope with our new President-Elect.

Thank you for choosing our dad to write about. He was a remarkable human being and I am very lucky and proud to be his daughter.

Dear Lisa, I’m so glad that you enjoyed my piece about your father. I hope I did his invaluable story and memory justice.