Kristie Sanchez

Professor Hernández-Ojeda

HONS 2011J

12/18/20

Abraham “Abe” Osheroff

Personal Statement

Prior to taking this course on the Spanish Civil War, I had never heard of the Spanish Civil War. It was not until I watched the documentary The Good Fight that I realized the significance of this event and what the Lincoln volunteers did. In the class, we studied literature, art and film that preserve the memory of the Spanish Civil War in a number of ways. Many of the works we studied were thought provoking, emotional and informative. They were nothing short of memorable.

As a final project we had to choose a Lincoln volunteer whose life we would study. Initially, I chose Abraham “Abe” Osheroff as the Abraham Lincoln volunteer to research, because I was interested in how he was from New York, and how he did his undergraduate studies at the City University of New York (CUNY), where I am also a student. As I began to do more research, I was able to find more information about his motivations and the extent of his activism after the Spanish Civil War. In addition to the written assignment, we also had to conduct an interview with a family member. I had the opportunity to interview one of Abe Osheroff’s children, Dov Osheroff. It was only after this interview, watching a series of interviews Abe had done over the years, and watching Abe’s documentary, Dreams and Nightmares, that I truly began to understand who Abe Osheroff was as well as his motivation for going to fight in the Spanish Civil War and living a life driven by activism. Abe Osheroff wanted to help people. He cared about the individual.

Before the Spanish Civil War:

Abraham “Abe” Osheroff was born in Brownsville, Brooklyn in 1915. His parents were Russian and Jewish and had immigrated to the United States. His mother was a seamstress, and his father was a carpenter. Brownsville was a working-class neighborhood where there were strong socialist sentiments. His mother and father were not religious and not very political (John Gerassi Oral History Collection). Osheroff, on the other hand, was political from a young age. His political involvement began when he was twelve years old, when he witnessed the protest against the conviction of Sacco and Vanzetti (Martin 2008). Osheroff said in an interview, “As my mother would say, if there’s trouble, that’s where he’ll be” (Roberts 2011). As a teenager, he witnessed the Great Depression that caused massive unemployment which largely affected his community. This environment garnered an interest in union organizing and his activism grew. In one instance, a neighborhood leftist recruited him and his friends to help evicted tenants by carrying the furniture landlords dumped out on the streets back into the rented apartments (Roberts 2011). At one point, he was arrested and beat up by police, but the landlords stopped the eviction of the tenants. Osheroff was in many ways enraged by the deep inequalities he saw. Activism became his outlet.

As a teenager, Osheroff joined the Communist Youth League. He felt that of all the parties, the communists “made the most sense” (Interview with Dov Osheroff), when it came to talking about class structure, and economic structure. He attended college at CUNY-City College of New York, where he majored in science but graduated with a social science degree (John Gerassi Oral History Collection). In college he engaged in protests such as compelling the president of City College to step down. After college, he worked a couple of jobs, but was mostly a carpenter. It was at this time that he also wanted to be a “full-time left activist” (John Gerassi Oral History Collection). He organized unions in Pennsylvania and in the Midwest. It was around this time that the situation in Spain was getting serious, and Osheroff was at a crossroads whether he should go to Spain or not. Osheroff was 21 years old.

Initially, Osheroff tried hard not to go to Spain. He was in love for the first time. Once he saw the newsreels of the footage of the bombing of the city of Guernica, he simply knew he had to go. By that time, Osheroff was a well-established member in the Communist Youth League. He was well known in his community. Osheroff in numerous interviews had stressed how guilty he would have probably felt if he did not go. He had also stated, “I wanted to close a gap between who I was and what I wanted to be” (John Gerassi Oral History Collection). In May of 1937, he was on a boat to Spain, without telling his mother. She thought he was organizing union protests in the Midwest. Osheroff even pre-made letters so she would not find out he was in Spain (John Gerassi Oral History Collection).

Abe Osheroff, 22, in 1937 (Stroum Center for Jewish Studies- University of Washington)

Involvement in the Spanish Civil War

In many ways, Osheroff did not go to the war, the war came to him. While on the ship to Spain, an Italian submarine torpedoed the ship he was on. Many people were killed in the attack, but Osheroff survived. He had to swim to the shores of Barcelona. Osheroff recounted how the conditions within the brigades were brutal. There was a shortage of food, weapons and supplies. Osheroff stated, “I personally never thought we would win… but it was important to keep fighting” (John Gerassi Oral History Collection). In a letter about why he went to fight in the war, he writes, “Today the majority of the American people understand the necessity for lifting the embargo on democratic Spain. If our only contribution was to help bring about this understanding, then we have no regrets” (2020 ALBA Online Gala). Osheroff feared that he would not get to return home. However, in the summer of 1938, Osheroff was sent back to America because he had been shot in the knee. Osheroff felt sad, anxious to get home, and relieved that he was going to live (John Gerassi Oral History Collection). Shortly after he left, Franco had his victory parade, and the other Lincolns were sent home. “The pain of that loss never leaves you” (The Good Fight, 1984).

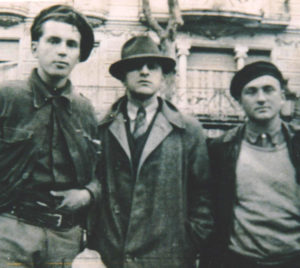

Abe Osheroff in 1938 (left) (Stroum Center for Jewish Studies-University of Washington)

After the Spanish Civil War

Osheroff never regretted going to Spain, despite having lost the war. If anything, it fueled the activism over the course of his life. Perhaps that loss he felt from losing the Spanish Civil War made him continue fighting the good fight.

He was not questioned when he came back from Spain, if anything he was welcomed back in his community and he went to the Bronx for the first time (John Gerassi Oral History Collection). Shortly after World War Two began, he enlisted to join the infantry. Osheroff, like many of the other veterans of the Spanish Civil War, saw World War Two as an extension of the Spanish Civil War. However, after the end of World War Two, Hitler fell, Mussolini fell, yet Franco stayed in power. Fascism did not end after World War Two.

In 1947, Osheroff became a full-time functionary for the Communist Party, however this role only lasted one year. He recalls the role making him “physically and spiritually sick” (John Gerassi Oral History Collection). He was not fond of inner-party life, rather, he liked to work with the people. He felt that the talk of party functionaries was disconnected from reality. By this time, McCarthyism had also begun in the United States. Osheroff went into hiding (John Gerassi Oral History Collection). He left Brownsville, and travelled to different places, changing his identity and working in different jobs. By the time McCarthyism was over, Osheroff had become very disillusioned with the Communist Party.

Earlier in his life, Osheroff was devoted to the Communist Party. As he heard of the numerous human rights abuses committed by the Soviet Union, particularly in the Hungarian Revolution, Osheroff’s devotion turned to disillusionment. Osheroff felt that the Communist Party cared about the masses but did not care about individual people (John Gerassi Oral History Collection), which is whom he cared about. In 1956, at the National Convention of the Communist Party, he left the party for good. He was forced to cut ties with his peers and close friends which was difficult. He was reprimanded. After this, he left Brownsville for good and went to live in California.

At first, Abe Osheroff felt that the Communist Party represented the causes he cared about. He did not like being in the internal bureaucratic leadership of the party. Eventually, he felt, “… it was like the CP left us, not us leaving the party” (Interview Robert Jensen 2005). Instead of being a Communist, Osheroff described himself as a radical humanist. According to his son, Dov Osheroff, radical humanism was more-so, “an anarchistic philosophy in which there was a sense of direction rather than an ideology” (Interview with Dov Osheroff), or an end goal. If anything, it was a way to, “…examine any proposal on the basis of how it affects people” (Interview with Dov Osheroff). Also part of Abe’s guiding philosophy was the role of empathy.

“If you look out the window and see a hungry, emaciated child and do not feel — not just pain, but a desire to do something to make the world a little better — then you’re not a complete human being, in my book anyway. There’s something missing in you that makes a person complete — empathy, compassion, the ability to feel the pain of another, whatever you want to call it. That’s the starting point. From there you have to do something about what you feel” (Interview Robert Jensen 2005).

This captured the essence of Osheroff’s activism, before, during, and after the Spanish Civil War.

In the early 1960s, Osheroff became involved with the Civil Rights Movement. He began by raising funds. However, he felt a calling to do more. In 1964, he went to Mississippi and was there for Freedom Summer, where he helped build a community center and even helped register black citizens to vote (John Gerassi Oral History Collection).

In 1966, after the Palomares incident in Spain, Osheroff’s interest in Spain rekindled (Dreams and Nightmares, 1974). The Palomares incident involved an American B-52 plane that “exploded over Spain and dropped four hydrogen bombs near the tiny village of Palomares” (History.com). At this time, Spain secretly shared an agreement with the United States, where the United States had atomic bases in Spain. Knowing this made Osheroff want to learn everything about Spain and how the United States was essentially keeping General Francisco Franco in power, even after fascism had ended in Germany and Italy. This spark led Osheroff back to Spain, almost 30 years after having fought in the Spanish Civil War.

Osheroff’s return to Spain is captured in his documentary, Dreams and Nightmares which was released in 1974. Upon arriving in Spain he retraced the trail that the Lincoln volunteers had walked. He wanted to look for any remnants of the war. He found nothing, until he came to Belchite. Osheroff described arriving in Belchite at that moment as a “religious experience” (Dreams and Nightmares, 1974). The film depicts how many Spanish people were actually happy with the Franco regime because it was a very prosperous time in Spain. He wanted to see if there was any secret opposition in Spain. The deeper he looked, the more he saw an elaborate opposition to Franco that was growing. He found worker-priests and underground unions. He even saw a survey where 97% of the Spanish people would vote Franco out of power (Dreams and Nightmares, 1974). However, the suppression of this opposition as well as the help of western countries like the United States, were also to blame. The film ends on a melancholic note when Osheroff states, “Why must all our dreams turn to nightmares?” (Dreams and Nightmares, 1974). However, this only means that the good fight is never truly over, and this is clear when Osheroff returned to the United States. This film won many prizes. When he came back to the United States, “He used the movie… as an entree to teaching jobs at the University of California, Los Angeles and the University of Washington, and to countless speaking engagements at colleges, high schools and other forums across the nation” (Martin 2008). Despite his recognition, he continued to work as a carpenter.

Osheroff’s activism extended into the classroom. Teaching at UCLA as a part time professor, he taught a course on the origins and aftermath of the Spanish Civil War. Rather than simply teaching what was already known, he wanted to instill in his students a methodology for how one understands history. Essentially, challenging students to think and question the things they hold as true. Instilling in them to ask how? and why? (John Gerassi Oral History Collection).

Osheroff, aside from teaching students, taught and learned from his own kids. During the Ronald Reagan presidency, Osheroff had not been as politically active due to things in his personal life. Dov Osheroff on the other hand, was very politically active. As Dov Osheroff recalled in the interview, Dov was active in the anti-apartheid movement as well as showing solidarity with the many Central American movements. At that point Abe would talk about how it was better in the old days. In many ways, Dov questioned why it was that his father would talk but not do anything. The two would bicker, and one day Abe called Dov and asked about forming a work brigade and going to Nicaragua. Once he began to look into the situation in Nicaragua, Dov mentions how “he [Abe] started to see the parallels to Spain” [29]. Abe Osheroff went with his two sons to Nicaragua in 1985 to help build houses in solidarity with the Sandinistas.

Abe spent the rest of his years living in the state of Washington. In 2000, he released a second documentary called, “Art in the Struggle for Freedom” about the poetry and posters of the Spanish Civil War. Though Abe might have been displeased being called an artist, he used film almost as a way to capture what could not be expressed through speech or through text. His son Dov recalls how he caught Abe singing in Yiddish once, and he sang really well. Abe was also fond of poetry, particularly Antonio Machado (Interview with Dov Osheroff).

Conclusion

What I learned about Abe, is that he simply wanted to help people. Having grown up and lived in a tumultuous time, he simply could not be indifferent to the injustices occurring around him. Abe Osheroff was not only a member of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade that fought in the Spanish Civil War. Among other things, he was an activist, a carpenter, a father and a storyteller. Abe Osheroff was a hero, always fighting the good fight. In an interview with Robert Jensen, Abe Osheroff when asked what the word authenticity meant to him said,

“Authenticity is incredibly important. To me, authenticity comes when your thoughts, your words, and your deeds have some relation to each other. It comes when there’s a real organic relationship between the way you think, the way you talk, and the way you act. You have to fight for authenticity all the time in this world, and if you don’t fight for it you will get derailed” (Interview Robert Jensen 2005).

As I move forward in my academic career and think about the values I hold, I aspire to live authentically as well. I admire Abe’s heroism and passion to help others. In the tumultuous time that we are living in, in 2020, the example of someone like Abe Osheroff is timely and necessary.

Works Cited:

1. “American Jews in the Spanish Civil War: Abe Osheroff.” UW Stroum Center for Jewish Studies, 3 Sept. 2018, jewishstudies.washington.edu/american-jews-spanish-civil-war/abe-osheroff/. Date Accessed: Dec. 17, 2020 2. ALBA A 18-156, ALBA A 18-157, Box 1 (1980) John Gerassi Oral History Collection; ALBA.AUDIO.018;Tamiment Library/Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University. http://digitaltamiment.hosting.nyu.edu/s/albafilms/item/320. Date Accessed: Dec. 17, 2020

3. Dreams and Nightmares (1974) by Abe Osheroff (documentary)

4. Jensen, Robert W. ABE OSHEROFF: On the joys and risks of living in the empire An interview with Robert Jensen. (2005), http://robertwjensen.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Abe-Osheroff-interview-by-Robert-Jensen.pdf. Date Accessed: Dec. 17, 2020

5. Martin, Douglas. “Abe Osheroff, Veteran of Abraham Lincoln Brigade, Dies at 92.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 11 Apr. 2008, www.nytimes.com/2008/04/11/us/11osheroff.html. Date Accessed: Dec. 17, 2020

6. Noel Buckner, Mary Dore, Sam Sills ; narrated by Studs Terkel ; narration co-author, Robert Rosenstone. The Good Fight : the Abraham Lincoln Brigade in the Spanish Civil War : a Film. New York, NY :Kino on Video, 1984

7. Osheroff, Dov. Personal Interview. 20 Nov 2020

8. Roberts, Gregory. From Spanish Civil War to Iraq, Activist Abe Osheroff Looks Back. 30 Jan. 12, 2004. Updated: Mar. 2011, www.seattlepi.com/local/article/From-Spanish-Civil-War-to-Iraq-activist-Abe-1134367.php. Date Accessed: Dec. 17, 2020

9. 2020 ALBA Online Gala (video)- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cVrsrxKyXvU Date Accessed: Dec. 17, 2020