Laura Alvim

HONS 2011J

Final Essay

Professor Hernández-Ojeda

Leo Eloesser, MD

Personal Statement

As an aspiring doctor and surgeon, I was very interested in the experience of doctors who volunteered in the Spanish Civil War and their practice of war medicine. While doing some research on the American Medical Bureau (AMB) – the medical corps associated with the Abraham Lincoln Brigade-, I came across Dr. Leo Eloesser, a thoracic surgeon from the San Francisco General Hospital. Dr. Eloesser’s commitment to global medicine captivated me. He was devoted to helping the people who needed him the most, independently of their geographic location, attending and teaching underserved communities all over the world. His exceptional language learning abilities allowed him to master nine different languages, facilitating his communication with the natives of the multiple countries he lived and worked at. He was also a musician and passionate about the arts, having many notable artists in his friendship circle, including Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo. Eloesser’s compassion, humbleness, commitment to service, and global social justice turned his life into an extraordinary adventure filled with striking achievements that serve as an inspiration for me as a person and as a future doctor. In this essay, I will tell his story, highlighting his participation and experience as an American medical volunteer in the frontline of the Spanish Civil War, and I hope that other readers will be just as inspired by his character as I was.

—————————————————–

“What better end could any man have than this fellow member of ours, who spent his life and met his death in the service of his ideals – Humanity and Freedom.” – Dr. Leo Eloesser (qtd. in Tsou and Tsou)

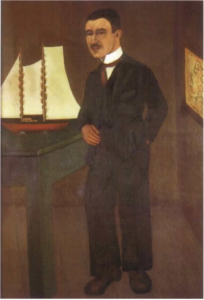

Fig. 1. Frida Khalo. Portrait of Dr. Leo Eloesser. 1931. Oil on canvas. Estate of Dr. Leo Eloesser. https://www.fridakahlo.org/portrait-of-dr-leo-eloesser.jsp

Introduction to Dr. Leo Eloesser

Leo Eloesser was born in the city of San Francisco in the year of 1881. Both his parents, Arthur and Molly Heynemann Eloesser, were children of German immigrants. Eloesser came from a wealthy family as his father conceived and manufactured “Can’t Bust ‘Em” overalls in 1864, at the same time his competitor Levis Strauss was popularizing denim jeans. Music had a strong presence in the Eloesser family, as Arthur Eloesser was a pianist and encouraged his kids to study music. Initially, Leo Eloesser wanted to pursue music as a career. It was a family friend, the ophthalmologist Dr. Adolph Barkan, who persuaded Eloesser to pursue medicine instead.

At the beginning of his studies at the University of California at Berkeley, Eloesser failed almost all of his courses as he prioritized his music over his academics. As he puts it, “Music filled my head; I wandered about alone, I lived in a world apart.” (qtd. in Scannell 236). He was only able to successfully complete his Bachelor of Science after his father intervened. Once that happened, Eloesser became a serious student, graduating with honors in 1900. At the insistence of Dr. Barkan, he then went to study medicine at the University of Heidelberg in Germany upon his graduation from UC Berkeley. In Germany, Eloesser was fascinated with the academic freedom of the country’s teaching system; students were only required to pass a series of examinations, and attendance was disregarded. This system gave him the freedom to explore his passion for music at the same time. He graduated with his medical degree in 1907, worked in Germany for the following two years, and spent six months in England working at St. Mary’s Hospital in Sir Almoth Wright’s laboratory.

Dr. Eloesser returned to San Francisco in 1909. While waiting for the six months required to validate his medical license in America, he volunteered on the UC Service at San Francisco City and County Hospital. He then opened his private practice in the city, which he claims took ten years until he was able to collect sufficient fees to pay the office rent. According to his colleagues, the private practice was struggling financially because Dr. Eloesser only charged a small portion of his patients, and charged very little from those who paid. He only became financially independent in 1914, when he told his dad he no longer needed monthly checks from him. In 1912 he joined the faculty of the Stanford School of Medicine as an Instructor. Due to his exposure to the German system, Eloesser was a courageous surgeon, undertaking procedures that many surgeons would not. Although some of these operations were bold and risky, he often succeeded in doing them.

Eloesser is described as a man of small build, slightly over 5 feet tall, with “an intense look, a penetrating gaze that could skewer any mortal, and an extremely caustic tongue.” (Blaisdell et al. 11). He was extremely dedicated and expected others to follow suit. Dr. Eloesser’s fame came primarily from his refined diagnostic skills rather than his surgical technique. He was an outstanding scientific writer, publishing a total of 92 articles – the majority of them being on chest surgery. He was also a distinguished teacher, and emphasized critical thinking and analysis rather than memorization. As he puts it, “I think that we all agree, in theory if not in practice, that trying to impart facts to students is futile, especially trying to impart them by word of mouth. Anyone in search of facts can find facts out by himself if he wants to.” (qtd. in Blaisdell). Eloesser pushed his students to look beyond the physical examination, diagnosis, and treatment; he wanted them to get to the core of the puzzle, unravel what was wrong anatomically, the basis of the disease, and the cause of death in cases where the patient passed. As a doctor, he was loved by his patients, who appreciated his compassionate care and thorough evaluations. They fully trusted his decisions and knew they could count on him to be there when they needed it. Dr. Eloesser was very dedicated to his patients, working Monday to Saturday, and seeing patients in his office until midnight, never turning anyone away.

The onset of World War I marked the beginning of Leo Eloesser’s global citizenship. As soon as the war broke out, he contacted his old chief in Germany, Professor Czerny, and went there to serve as the head of a surgical division in a large German hospital. There he published a few papers about War medicine, including the use of blood transfusions and the management of gas infections. When the United States was about to enter the war, after the sinking of Lusitania, he returned to America and tried to join the US army. He expected that the American military would gladly welcome his previous experience with casualty management in the war; however, his connection with Germany led to his denial. Dr. Eloesser still managed to get the supervisor role in a large orthopedic and rehabilitation ward at Letterman Army General Hospital. When the Army showed resistance to building a prosthesis center, he went to Mare Island to borrow machinery from the Navy in order to set up an artificial limb factory for the many amputees in his ward. The factory was successful in producing the “Letterman leg,” and Dr. Eloesser himself pioneered the fitting of these prostheses. He always went above and beyond for his patients, ensuring all their needs were taken care of. His dedication was restless, and he continued to attend patients at San Francisco County Hospital at night while serving at the Letterman Army General Hospital.

Once the war was over, he returned to his assistant chief position at Stanford’s County Surgical Service and reopened his private office. After an influx of patients with lung diseases during the 1919 influenza epidemic, Dr. Eloesser became more interested in thoracic surgery, especially in treating tuberculosis. He conceived a flap, known as the Eloesser flap, used for the drainage of empyema and treatment of tuberculosis when there was no effective medication for it. Continuing his involvement with global medicine, Dr. Eloesser went to Moscow in 1934, where he established the first Russian Thoracic Surgery clinic. A few years later, after serving as President of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Eloesser packed his bags once again and went to Spain in 1937 to help the Republican side in the Spanish Civil War.

The Spanish Civil War

In July of 1936, General Francisco Franco led a military uprising to take down Spain’s democratically elected government. The rebels expected to take control of the country in a few days, but the failed coup gave rise to a bloody civil war that lasted three years. Franco’s rebels became known as the Nationalists; they were supported by the conservative, religious, and military Spanish elite, who had their power and privilege threatened by the progressive reforms that took place in the Second Spanish Republic. Those in the resistance became known as the Republicans, and most of them were farmers, urban workers, and middle-class; they fought to defend the Popular Front government that was currently in power and protect their democracy from the fascist forces.

The conflict took international proportions with fascist Italy and Nazi Germany supporting the Nationalists, and the Soviet Union and Internation Brigades aiding the Republicans. The United States, along with other Western nations, adopted a non-intervention policy concerning the Spanish Civil War. Many Americans, seeing the growing threat of fascism and the need to stop Hitler, were very disappointed in the country’s positioning. They decided to take matters into their own hands and volunteered to go to Spain to aid the Republican’s fight for democracy. The International Brigade formed by American volunteers was named the Abraham Lincoln Brigade.

Dr. Leo Eloesser was one of these volunteers, deciding to go to Spain in September 1937. As he told the San Francisco Chronicle newspaper, “I wanted to help the loyalist cause and the best way that I see to do so is to offer my services to the stricken in Spain.” (qtd. in Tsou and Tsou). While the majority of volunteers was very young (some were still in their teens), Dr. Eloesser was 56 years old by the time he went to Spain, which shows his tremendous humanitarian energy and lifelong commitment to fighting for his ideals. He gathered a group of volunteers among the Pacific coast medical professionals to go with him and raised $50,000 in private donations to finance an ambulance and a hospital unit to take to Spain. He presided over a meeting of the American Association of Thoracic Surgery and then left for Europe with his viola in November of 1937.

Eloesser’s experience and skills were put to great use at the war front on Teruel. He set up mobile field hospitals, developed a blood bank, and served on battlefields for eight months. In a letter to the Medical Bureau to Aid Spanish Democracy (AMB), the medical and nursing corps associated with the Lincoln Battalion, Dr. Eloesser describes in detail how the scarcity of hospital beds, ambulances, light sources, and the cold were prominent issues in the medical units at the war front. After leaving Teruel to return to Barcelona on December 26th, his group got orders to return to the front on New Year’s Day. “Our equipment was no better than when we left the first time- somewhat worse in fact, for we had expended some material and intervening holidays had interrupted our replacements. […]. We began to unpack our things and set up. No sooner had we done so than the wounded began to come in, so that for the first two days we worked right through, both we and the Spanish outfit who worked with us.” (Eloesser 2).

The field hospital was set up in a villa once owned by the family of a Valencia doctor. With no heat, stone floors, and broken windows due to previous bombing raids, the field hospital wards were freezing. Medical personnel would lay mattresses on the floor near the stove to place the worst-shocked patients, hoping that they would find at least a little bit of warmth. Candles and pocket flashlamps (while their batteries lasted) became the primary sources of light as air raids would put down the power line. Surgical material had to be sterilized on a kitchen stove fueled by any available piece of wood, as coal and alcohol were running out. There were few ambulances, and the strained Spanish roads made it harder to transport patients, so they would only arrive at the treatment center at night, and sometimes they would not make it through the trip. Even supplies that we take for granted, such as cups, were non-existing at the field hospital, and patients would drink out of condensed milk cans. As Dr. Eloesser put it, “it may be hard to picture such a hospital to anybody who hasn’t seen one working.” (3).

Fig. 2. Dr. Leo Eloesser (right) operating on a patient in Spain in 1937, at the height of the Spanish civil war. 1937. Tamiment Library, New York. www.scmp.com/magazines/post-magazine/long-reads/article/2156128/medical-marco-polo-american-doctor-who-fought. Web. Accessed 15 Dec. 2020.

As one can imagine, carrying out a surgical procedure in these conditions was a challenging mission. As the battle went on, doctors and nurses spent multiple sleepless nights working in the worst possible conditions to save the many injured soldiers. In his letter to the AMB, Dr. Eloesser wrote: “the self-evident question is, of course, ‘Why do you put up with this, and why don’t you get what is needed?’ And the answer to that is: ‘To have what is needed takes time and money and means of transportation. Money can be got sooner or later, come way or another. Time can’t, and when wounded begin to pour in, one has to take things as they are and make the best of them and leave improvements until later. As for transportation, you may understand why I am clamoring so loud, long, and insistently for a Ford carryall with a light delivery truck.” (Eloesser 5). Their creativity to deal with the dwindling resources, their constant pushing for improving current hospital conditions, and their resilience were commendable, much like that of the frontline workers on the current battle against the COVID pandemic. Eloesser closes his letter with a story from the surgeon general about the aftermath of a field hospital bombing that epitomizes the devastation caused by the war; “I regret to have to report that I am leaving eight wounded behind: my stretcher bearers and personnel have all been killed or wounded and I have no one left to help me carry the men out.” (qtd. in Eloesser 14).

From his experience treating the wounded in the Spanish Civil War, Dr. Eloesser wrote an article on the treatment of compound fractures during the war, highlighting the effect of new war mechanisms such as the extensive use of airplanes. His article, “Treatment of Compound Fractures in War: reports of practical experience in the Spanish Civil War,” was published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in November of 1940. While in Spain, he remained in touch with his patients in San Francisco, exchanging letters with them with updates on the war development. Highlighting Eloesser’s insatiable humanitarian spirit, one of his correspondents replied, “it would appear that you have been working extraordinarily hard and I am afraid that you will need a real holiday after you leave Spain. It seems a pity at your time of life that you should work so hard, but I don’t believe you would ever be happy unless you were.” (Rogers 1). In 1938, the International Brigades were withdrawn from the war by Spanish prime minister, Juan Negrin, in the idle hope that the Nationalists would withdraw their Germans and Italian troops in return; the Republicans lost the war by 1939, and Franco’s dictatorship began. By the end of 1938, Dr. Eloesser returned to San Francisco and resumed his duties at the City and County Hospital and private practice. Still, his humanitarian trips and global health accomplishments were not over yet.

Life after the Spanish Civil War

When the Second World War broke, Eloesser once again offered his war medicine expertise to the United States Army. However, the American troops denied his participation due to his involvement in the Spanish Civil War. In his unpublished memoir he noted, “I was on the blacklist; ‘Premature Anti-Fascist’ it was called. I’d been in Spain. Anyone who had been in Spain was a Communist.” (qtd. in Tsou and Tsou). So for the duration of World War II, Dr. Eloesser continued working in San Francisco until 1945. That year Eloesser joined the United Nations Relief Organization as a surgery specialist and went to China in August.

In China, he was very disappointed with the corruption in the Chiang Kai-shek regime and made his way into Mao’s remote communist stronghold in Yanan. He worked with them for four years, leaving like the peasants while teaching hygiene, sanitation, and midwifery to the “barefoot doctors.” He believed that poor sanitation, dirty water, and the diseases transmitted by insect bites were among the leading causes of death in China. There he also partnered with the World Health Organization and taught local medical students at the Bethune Medical School founded by the Canadian surgeon, Norman Bethune, who met Eloesser in Spain while supporting the Republican forces during the Civil War. Through his work there, Eloesser added Chinese to his extensive language repertoire and wrote a manual for rural midwives titled Pregnancy, Childbirth and the Newborn, written entirely in Chinese. The book was later revised, translated, and published in 3 other languages: Spanish, English, and Portuguese.

At the end of 1949, after the UN refused to acknowledge the new People’s Republic, the UNICEF withdrew from China, and Dr. Eloesser returned to the US. He continued to work with the UNICEF, becoming increasingly interested in health care in third world countries. At 70 years old, he met his lifelong partner in San Francisco, Joyce Campbell. Like many other American volunteers who fought in Spain, Eloesser was persecuted during the McCarthy anti-Communist era in the United States. As a result, he decided to leave the country, moving to a small town in Mexico called Tacambaro. There he continued his international humanitarian service, setting up a clinic to treat the underprivileged peasants of the area, teaching at the Pabellon de Cirugia of the Sanitario de Huipulco and the Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Respiratorias, and establishing a curriculum to train rural midwives. Eloesser later gained Mexican citizenship and was awarded the Presidential Medal for his charitable work in the country. He died of a heart attack just three months later, on October 4th of 1976, after 95 very well-lived years. He was honored by his cellist friend, Bonnie Hampton, who played his favorite Beethoven and Mozart quartets in a ceremony at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music on November 30th.

——————————————————

“Health is the right of everyone, and not a privilege of a favored few. Health of the people can be achieved. Achieved not by complicated and costly methods of surgical operations done in the ivory towers of electrically equipped and air-conditioned operating rooms, but by ordinary means within the grasp of everyman; by killing flies and lice, by properly disposing sewage, by cleanliness and decent living” – Dr. Leo Eloesser (qtd. in Tsou and Tsou)

Sources

“Biographical Note.” Register of Leo D. Eloesser Papers, Lane Medical Archives, Stanford University Medical Center, lane.stanford.edu/elane/aid/20_Eloesser/index.htm.

Blaisdell, William. “Leo Eloesser: The Remarkable Story of a Medical Volunteer in Spain.” The Volunteer, 3 Dec. 2016, albavolunteer.org/2016/12/leo-eloesser-the-remarkable-story-of-a-medical-volunteer-in-spain/.

Blaisdell, William et al. “The Brunn–Rixford–Eloesser Years: 1915–1945.” The History of the Surgical Service at San Francisco General Hospital, Robert Albo, 2007, pp. 10–14, zsfgsurgery.ucsf.edu/media/234872/history%20of%20sfgh.pdf.

Caen, Herb. “Dr. Leo Eloesser.” California Monthly, Dec. 1976, p. 22. Box 7, Folder 6. Series I: Medical Personnel: Biographical Files and Correspondence, 1936-1988. Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University, New York, NY. 22 Oct. 2020.

Eloesser, Leo. “Letter Received From Dr. Leo Eloesser .” Received by Medical Bureau to Aid Spanish Democracy, 22 Jan. 1938. Box 7, Folder 12. Series I: Medical Personnel: Biographical Files and Correspondence, 1936-1988. Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University, New York, NY. 22 Oct. 2020.

Rogers, William L. “Dear Doctor.” Received by Dr. Leo Eloesser, 490 Post Street, 5 May 1938, San Francisco, CA. Box 7, Folder 12. Series I: Medical Personnel: Biographical Files and Correspondence, 1936-1988. Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University, New York, NY. 22 Oct. 2020.

Scannell, J. Gordon. “Leo Eloesser, MD—Eulogy for a Free Spirit.” Annals of Surgery vol. 198,2 (1983): 235–238. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1353090/?page=3.

Tsou, Hwei-Ru, and Tsou, Len. “’Medical Marco Polo’: American Doctor Who Lost His Heart to China.” South China Morning Post, 27 July 2018, www.scmp.com/magazines/post-magazine/long-reads/article/2156128/medical-marco-polo-american-doctor-who-fought.